Chapter 3: Variables and Other Basics

As we use high level programming languages to write our programs, we learn that programming languages specialize in abstraction. Abstraction is a way of hiding irrelevant detail and focusing on the things that matter. Programming languages focus our attention on algorithms and the data we need to power those algorithms, ignoring the actual details of making those algorithms work on specific CPU architectures.

We start looking at the C programming language by working with abstractions of computer memory. Variables are abstractions of memory words; when we work with variables, we are really working with memory. But the gory details of how we are working with memory are hidden and we are left with the niceties that we get in C.

We will start out by defining variables and how we work them. We will also need to define data types, as they are central to how we work with variables. We will also look at the unique ways C lets us manipulate memory through variables, and we will look at how this all works in a Pebble smartwatch.

Defining Variables

Variables are symbols that stand for words in a computer's memory. As such, they have a value that can be set and that is remembered until it is changed. That value can also be referenced for use in computations.

Let's take an example.

miles = 230;

gallons = 12;

milesPerGallon = miles / gallons;

In this simple example, we are working with three variables, which stand for three memory words. The first two lines assign values to two variables; the third line uses the values we assigned to compute and assign a value to a third variable.

In the example, we used a number of operators to manipulate values of variables. Which operator we may use depends on the kind of value we are using (see the next section on data types for more), but the assignment operator is always defined for all variables. The assignment operator takes the value on the right of the "=" sign and makes it the value of the variable on the left of the "=" sign. When a variable is referenced on the right of the "=" operator, it gives up its value. So when the third line in the above example is executed, it's the same as as executing milesPerGallon = 230 / 12.

Let's consider another example:

positionX = 72;

positionY = 25;

acceleration = 1;

x_velocity = 3;

y_velocity = x_velocity;

First, note that there are rules for variable names. Variables names must be comprised of a combination letters, numbers, and an underscore ("_"). They must start with either a letter or an underscore and they may be of any length. By convention, as in the example above, variable names that could logically be made up of multiple words ("x velocity") are given a name with an underscore replacing any spaces (x_velocity).

Second, note that C is case-sensitive when it comes to variable names. This means that capital letters are considered different than lowercase letters. positionX is not the same variable as positionx.

It is indeed possible to use a variable without first assigning it a value. However, remember that variables are simply abstractions for memory words. The result of using a variable without initializing is an unpredictable value; you get whatever was left over in memory from the last time the memory word was used. Programmers often incorrectly assume that variables are automatically initialized to zero when a program starts; it is actually best to assume that any left over data is just useless.

Different Compiler Behavior

Sometimes, C compilers behave differently with small details like using variables without initialization. There have been several attempts to standardize C, but compilers -- particularly the variety of open source compilers -- don't all adhere to the same standard. In addition, standards don't always address details like variable initialization. This leaves compiler writers free to choose. So, in regard to variable initialization, most compilers do not automatically initialize variables, but some do. Make sure you check your compiler before you rely on this behavior.

Data Types

Variables have two important properties: what values can be assigned to them and what operations can be done to them. Together, these two properties are called a data type. Every variable used in a C program must have a data type.

Consider the example code below:

int radius;

float pi;

double circumference;

Here, we have declared three variables: radius, which can take on integer values, pi, which can take on floating point values in memory words, and circumference, which take on floating point values that are double the size of other floating point values. Note that an integer is a whole number without any decimal points and a floating point number has a decimal point and is capable of representing fractional numbers. Note, too, that a variable must be declared before it is used in a C program; the C compiler must know what values and operations are to be used with a variable before it works with that variable.

Once we have declared the variables as in the example above, we can work with them like in this example:

radius = 23;

pi = 3.14159;

circumference = 2 * pi * radius;

Since pi can take on floating point (i.e., fractional) values, we can use a decimal point in its assignment.

Note that, given each variable's declaration, values outside the declared value set are considered an error. For example, trying to assign a floating point value to an integer variable would be flagged as an error:

radius = 23.1;

Since setting a variable to an initial value is such a common exercise, declarations allow assignments in the declaration statement. So, we can combine the above declaration and assignment examples like this:

int radius = 23;

float pi = 3.14159;

double circumference = 2 * pi * radius;

Literals

As we have seen, literals have a data type. The absence of a decimal point in a number usually indicates that the number is an integer. Likewise, the presence of a decimal point usually indicates that the number is a float data type.

However, there are ways of designating numbers that get around these assumptions. This typically means that you put a letter at the end of the number. For example, 23 is an integer, but 23L is a long integer and 23F is a floating point number.

The table below shows letter designations for data types and gives some examples.

| Literal | Declaring Keyword | Description | Example | Illegal Example |

| Integer | int |

A whole number in decimal, octal, or hexadecimal form. Integers can have prefixes that explain the base in which they are specified and suffixes that explain the type of the integer. | 23 23L 0x23 0o23L 0b1011 | 23.0 0o238 |

| Floating-Point | float |

A number with an integer part, a decimal point, a fractional part, and an exponent part. Floating point numbers can be expressed in decimal or exponential form. Suffixes of F or E are allowed to indicate floating-point or start exponent expression. | 15.6 156E-1 |

25. 100.0E |

| Double Floating-Point | double |

A floating point number with double the memory space for storage. | 15.6 156E-1 |

25. 100.0E |

| Character | char |

A representation of letters and other character data. Pebble smartwatches use UTF-8 representations for characters, so a single character might not fir into a `char` type. | 'A' '5' '#' |

"A" "string" |

| Boolean | int |

A representation of true and false values. Boolean operators are logical operators. | true false 1 0 |

"true" "false" T FALSE |

Other Basic Data Types

The table in the previous sections adds two data types to ones we have discussed. Character data types are declared with the char keyword and hold single-byte characters/symbols as their value. On a Pebble smartwatch, these values come from the Unicode character set. Unicode contains a Western style alphabet in the first 128 characters and a large collection of the other alphabets in the rest of the set. The UTF-8 encoding of Unicode, which Pebble uses, can use multiple bytes and therefore could expand into multiple chars. In fact, only the first 128 characters fit into a single char. Note that character data types include numbers as characters, so that '5' is not the same as 5. Character literals are represented using single quotes.

Characters are not Strings

It is useful to emphasize that char data types only hold a single-byte character (like "h"), not a string of characters or a multi-byte character (like "é"). Strings are not built into C as they are in some other languages. Strings are represented by arrays of characters -- sequences -- and will be discussed at length in Chapter 9.

Sometimes character data cannot be represented very easily. For example, how does C represent a newline character? A newline cannot appear in a character or string literal, but newlines are very useful. For these issues, C uses escape sequences. An escape sequence begins with an escape character and include either a letter or a number sequence to reference the characters Unicode value. The number sequence is useful to reference characters that do not have a symbol with which to refer to them.

Let's look at an example.

char letter = 'A';

char letter2 = 'a';

char letter3 = '\092';

char letter4 = letter + 32;

char letter5 = '\n';

int difference = letter2 - letter3;

The first three declarations are not unusual; we just defined character literals as having representations like these. Note that even letter3 has the same value as the previous 2 variables. The declaration of letter4 demonstrates type conversion. Technically, the + operator is not defined for characters, so letter has to be converted to an integer before addition. Then the type of the resulting expression (int) is converted back to char before assignment to letter4. When converting a character to an integer, the UTF-8 value of the character is used. This means that the last declaration declares difference to be an integer that has the value of 0. Finally, letter5 takes on the newline character, represented with an escape sequence.

The last basic data type in C isn't really a data type. C does not include the definition of a boolean type as most programming languages do. A boolean data type would take on the values true or false and use logical operators, such as and and or. C supports boolean operations, but does not have an explicit boolean type. This means that comparisons can generate boolean values, but C does not have boolean literals.

Notice the literal table in the last section. It lists 1 and 0 as boolean literals. C considers 0 to be false and non-zero values to be true. This means that the integer data type also serves as the boolean data type for C.

Consider this example:

int true=1, false=0;

int x, y;

x = true;

y = (x == true);

We can simulate boolean operations and values by using integer data types. In this example, x is treated as a boolean, and is given the value true, which makes sense because true is also an integer. However, y gets its value from a comparison, something that gives a true or false value. And that comparison value is assigned to an integer.

If we were to print the values of x and y, both would have the value 1, or true.

Let's look at another example, using the definitions of true and false from the previous example.

int retired = true;

int still_working = true;

int gets_a_pension = (retired && ! still_working) || (age > 65 && hours < 20);

This demonstrates a boolean expression, which is computed from boolean values. Boolean values come from variables or operations that give up boolean results. So retired takes on the value false (really 0 as the literal value), but gets_a_pension computes its value from boolean operations and comparison operations. Consider the table of boolean operators below

| Operator Name | Syntax | Meaning | Example |

| AND | a && b | Result is true when both operands are true | true && false (miles < traveled) && still_running |

| OR | a || b | Result is true when at least one of the operands is true | true || false (miles < traveled) || still_running |

| NOT | !a | Result is true when the operand is false; result is false when the operand is true | !true !(miles < traveled) |

Let's assume that age equals 70 and hours equals 25. We can then compute the expression as the figure below:

The final result of the expression in Figure 3.1 is false (or 0).

Using Boolean Types in Pebble Programs

Pebble programs already have definitions of a

booldata type, withtrueandfalsevalues (defined as1and0) built into them. If you want to use thebooldata type, therefore, you don't have to include these definitions into your code.

Type Conversion

There are many times when the values in one data type could be used with another data type. For example, the value 23 can be used for integer and floating point numbers. When the value of one type can be used for another, we say that the value is converted from one type to another. That value is converted before it is assigned. So, for example, consider the code below:

int radius = 23;

float pi = 3.14159;

float extra = 23;

double circumference = 2 * pi * radius;

In the first line, an integer is assigned to an integer variable. In the second line, a floating point number is assigned to a floating point variable. In the third line, however, an integer value is assigned to a floating point variable. Technically, this does not work: the two sides are different types. However, the integer type is type compatible with the floating point type and C automatically converts 23 to 23.0 and the assignment is made without problems.

The fourth line of the example is interesting. We have to determine the data type of the right hand computation in order to see if it can be assigned to the double floating point on the left. In C, the data type of expressions is determined by the data type that has the most values represented. So, in the example, the right hand side of the assignment takes on a floating point data type after converting 2 and the value of radius(23) to floating point. Then the expression is computed, giving a floating point result. Finally, the floating point result is converted to double and the assignment is made.

The point here is that conversions are necessary to follow the typing rules of C and, if it can happen, this conversion happens automatically. The data typing rules of C enforce a kind of data typing called static typing. Static typing dictates that the types of variables are derived once (at declaration) and do not change throughout the execution of a program.

Dynamic Data Typing

There are other data type rules. The opposite of static typing is dynamic typing. In dynamic typing, variables change their data type depending on the values assigned to them. Variables need no declaration because they have no initial data type. If the example above were dynamically typed, the last line does not convert the result to double before assignment, the variable takes on a float data type to match the right hand expression's data type.

Javascript is an example of a dynamically typed language. In Javascript, variables are declared, but they are simply declared as "var" to indicate they are variables. The data type of a variable is assigned when a value is assigned.

In C, variables are also strongly typed. This means that once variables are bound to a data type, they stay bound to that type. Which means that they cannot change types, but require other types to be converted to their data type before they are assigned.

Weak Data Typing

The opposite of strong typing is weak typing, where variables can change their data types during the execution of a program. PHP is an example of a weakly typed language. In PHP, you could execute

$peb = "a"; $peb = $peb + 2, which is an error in some languages. The variablepebin this case changes types from a character to an integer as the program executes.

Let's consider one more example.

angle = (angle + 1) % 360;

int dangle = TRIG_MAX_ANGLE * angle / 360;

Here, we see the use of the % operator -- the modulo or remainder operator -- and we have to decide about division. The modulo operator is an integer operator that produces the remainder of a division of the two operands. In this case, the variable angle will increment, then get divided by 360, with the remainder assigned back to angle. If this code were repeated many times, the value of angle would cycle between 0 and 360.

The division in the second line could produce one of several values, depending on the data type of the variables used. If we assume that this code does not produce an error, the declaration data type of int says that dangle needs an integer value and the right side had better produce it. That means that no part of the expression on the right should be of a floating point or double data type. The integer version of the division operator will discard any fractional result. This means that if the left side of the division is less than 360, the result will be 0.

Declaration Modifiers

Since variables are just abstractions of memory words, declarations in C provide information for the compiler about the size of memory word to use for the declared variable. C defines some declaration modifiers that provide a little more detail about the memory word that will be used to represent a variable. These modifiers are included in a variable's declaration.

As an example, consider the declarations below:

short int si;

unsigned char uc;

long double ld;

The short modifier tells C that, instead of a regular integer, the declaration only needs half of the space normally required. unsigned declares that the character may use one more bit to represent itself in memory (that bit is normally reserved as a sign bit; for characters, it is just reserved, but not used). The long modifier declares that the double-wide floating point number should be stored in space that is twice as long as that which is used for the double type.

A list of modifers is below.

| Modifier | Meaning | Examples |

short |

Halves the capacity of the data type, mostly in terms of possible values | short intshort short |

long |

Double the capacity of the data type, mostly in terms of possible values | long intlong long |

unsigned |

Use the sign bit of a number to store value, essentially doubling the values that can be used | unsigned intunsigned char |

const |

The declared variable is a constant. | const int top = 100const unsigned char A = 0x41; |

static |

The declared variable is allocated before code is run, and is not accessible outside the current file. | static int x_velocity;static float mortgage; |

A note should be made about the const modifier. Any variable declared with the const modifier must (a) include an initialization and (b) not be changed throughout the program.

Let's consider one more example.

short int position_x;

static int x_velocity;

const int ball_radius = 10;

The first representation here declares position_x as a "half integer". The actual size of the memory word depends on the CPU; for Pebble watches, integers are 32 bits wide. So, position_x is a 16 bit integer, which means it can have values between -32,768 and 32,767. The variable ball_radius is a constant, initialized to 10, and cannot be changed.

Note the last entry in the modifier table is static. Static variables are placed in memory words, allocated before a program is run and deallocated only at the end of the program. Normally, variables are allocated in memory when the block they are declared in is encountered by the program's execution (for more info on block, see the coming section on "Accessiblity Rules"). The fact that static variables are allocated once means that no matter how many times a block of code is encountered in a program's execution, the static variables in that block are allocated once. This is compared to the non-static variables, which are allocated again and again as a code block is executed.

Casting

There are times when C cannot determine the data type conversion that is needed or we want to force a conversion to take place. Consider the example below:

int total=100, number=50;

float percentage=0.0;

percentage = number / total * 100;

In this example, the division produces a value of the integer type: two integers are divided and C would consider the result an integer. Multiplication of two integers -- the division times 100 -- would also give an integer. The value is then converted to float and assignment operator assigns the value. The value that gets assigned is 0.

You might desire the result assigned to percentage to be 0.5. However, remember that all values on the right are integer, so the result is integer, and the integer division gives 0. If we wanted to force the floating point division, we would have to make one of the operands into a floating point. We could cast one of the operands this way:

percentage = (float)number / total * 100;

The type in parentheses converts the immediately adjacent value, which is, in this case, number. The result is a floating point value, because a floating point value (number) was included in the computation. The result of this expression is indeed 50.0.

Expressions and Precedence

When combinations of constants and variables are connected with operators, the result is called an expression. Expressions represent a computation, using the values represented to produce a single result value. That result has a data type that can be used just like single representations of literals or variables. In fact, we consider a single literal or variable as the most simple expression.

We have already seen simple expressions. In the example in the previous section, number / total * 100 represents an expression; two variables are combined with a division operation and multiplied by a third variable. The computation will result in a 0 value with an integer data type.

When we consider an expression, the order of operations is important. It is tempting to simply compute an expression in a left-to-right direction. Consider the expression below:

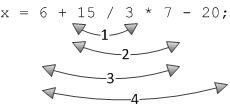

x = 6 + 15 / 3 * 7 - 20;

A left-to-right evaluation of the expression would yield a value of 22. However, C has a different order of evaluation. The rules that specify the order of evaluation are called precedence rules. A short set of precedence rules are given in the table below (a complete table is given in Appendix A).

| Precedence(s) | Operator |

| 1 | () |

| 2 | unary + -! |

| 3 | * / % |

| 4 | + - |

| 5 | comparison operators |

| 6 | assignment and shortcuts |

This means the result of the expression above is actually 28, evaluated in the order shown below:

Let's consider a more complicated example.

color_distance = sqrt( (red2 - red1) * (red2 - red1) + (green2 - green1) * (green2 - green1) + (blue2 - blue1) * (blue2 - blue1) );

The "color distance" between two pixels can be calculated as the square root of the summation of the squares of the differences between pixel color components. Note the parentheses. Those are done first, before the multiplication and division operators. So in this expression, the subtractions are done first, then the squaring/multiplications, then the additions.

Why Do We Have Precedence Rules?

After working through all the precedence rules for expression evaluation, one might ask why? Wouldn't it just be simpler to evaluate left to right? The short answer is YES! For humans, it is probably easier to evaluate expressions left to right.

However, it turns out that for compiler to parse through complicated C syntax, grouping operators into groups is actually makes it simpler and easier to parse. By defining programming languages using grammars, compilers process groups of operators as grammar definitions, and defining C using these definitions is a clean way to specify the language.

However, this is not a very satisfying reason and grouping like this seems arbitrary. Various sources actually claim that some rules -- say, multiplication before addition -- find their origin in how algebraic operations are expressed: ax + b seems to imply that ax should be computed first. This type of expression goes back to the 1400's; see this Web site for a review of early grouping symbols.

The truth is that we really don't have a reliable explanation as to where this came from. However, it's the rule now for C (as well as many other languages), so we deal with it.

We need to consider one more set of rules for expression evaluation. Associativity is a property of operators in the C language. For example, the expression 15 - - 2 might seem at first glance to be illegal, until one realizes that the righthand - sign is a negation operator and is associated with the 2 in the expression. Associativity plays a role in expression evaluation and is considered first before operator precedence.

The complete table of C precedence rules combined with associativity properties can be found in Appendix A.

Notation Shortcuts

There are a few notational shortcuts we can make in C. We can use them to shorten expressions and to relate algorithms more concisely.

Most shortcuts involve assignment. For example, instead of

x = x + 1;

we can use the shortcut of the increment operator like so:

x += 1;

This type of shortcut extends to several operators. The operators -=, %=, *=, and /= operate in the same way.

Two more shortcuts are used in C. As analogs to += and -= for increment and decrement operators, C includes ++ and --. Consider the following example:

x = 10;

x = x + 1;

x += 1;

x++;

After the first initialization, each following line increments x by 1.

y = 360;

y = y - 1;

y -= 1;

y--;

Again, after the first initialization, each following line decrements y by 1.

Just to make things more complicated, C specifies that these two operators can appear before or after another value in an expression. Therefore, we can have x++ as well as ++x in an expression. They are subtly different.

x++incrementsx, then evaluates to new value.++xevaluates to the value ofx, then increments the variable.

Let's look at an example.

int x = 10;

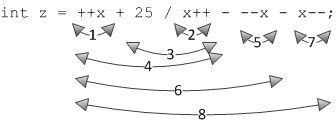

int z = ++x + 25 / x++ - --x - x--;

What is the resulting value of z? The computation goes as in Figure 3.3:

- increment

x, evaluatexto 11 - evaluate

xto 11, incrementxto 12 - perform integer division, giving 2

- perform the addition:

11 + 2giving 13 - decrement

x, evaluate to 10 - perform the subtraction:

13 - 10giving 3 - evaluate

xto 10, decrementx - evaluate the final subraction:

3 - 10, giving -7

The table below shows all the compound shortcuts in C.

| Operators | Description |

| += and -= | Addition and subtraction operators |

| *= and /= | Multiplication and division operators |

| %= | Modulo (remainder) operator |

| &=, |=, and ^= | Logical operators: and, or, and not |

| >>= and <<= | Shifting operators: right and left shifting |

Where Did These Shortcuts Come From?

The C programming language has a long history. In the days it was first developed and implemented, statements in C had a very close connection to the instructions that were generated by the C compiler. Therefore, machine language that was generated by the compiler had a strong effect on the syntax of the language. This means that

x++would generate one instruction and++xwould generate another. These forms begat other forms, both as instruction substitutes and programmer shorthand.

Statements and Control Flow

As we have been giving examples, we have been showing statements in C. A statement is a section of C code that -- for lack of a better term -- does something. It is a unit that performs an executable action. As we have seen them, statements are comprised of variables, literals, and operators. In future chapters, we will expand our idea of statements.

Note two special considerations about statements.

- Statements are terminated with a semicolon. We have seen this in the examples given so far in the chapter.

- Statements can be comprised of other statements. By using curly brackets --

{and}-- we can group several statements in one compound statement.

This means that this is a statement:

int miles = 0;

and this is a statement

{

radius = 14.1;

circumference = 2 * pi * radius;

}

The last form, that is, a compound statement counting as a statement, will be very useful as we consider more complex statements like conditional or looping statements.

A statement is actually an expression. This idea can lead to confusing C statements. As we will note later in this chapter, an assignment operator can indeed be an expression, so using an assignment operation as a statement makes sense. However, we could also just have expressions, as below:

x;

y < 2;

x++;

The last statement is often used. Since x++ is shorthand for x = x + 1, using either expression as a statement makes sense. However, the first two lines are confusing, even though they are legal.

The control in a C program is sequential. That is, unless otherwise directed by statements, execution in a program starts at the first statement and moves in sequential order from that statement until the last. There are many statements that redirect execution -- and we will examine them starting in the next chapter -- but underlying every statement is sequential control flow of a computer's program execution.

Accessibility Rules

Variables and other entities in C may be declared in many places. Because C is block structured, we can define names in many different blocks. For example, consider this:

int positionX = 10;

{

int positionY = positionX + 20;

float proportion = (float) positionY / positionZ;

}

int positionZ = positionY + porportion*positionX;

This is a bit contrived, but it makes a point. There are two blocks here: an outer block where the declarations of positionX and positionZ happen and an inner block where the declarations of positionY and proportion happen. The curly brackets are block delimiters.

Here are two rules about accessibility -- or scope -- of declared names in C:

- You must declare names before you use them.

- Code can only access names declared at the current block level and outer block levels.

These rules mean that names at inner block levels are inaccessible. So in the above example, the declaration of proportion that uses the variable positionZ is actually illegal; the use of both proportion and positionY in the declaration of positionZ is also illegal. The reference to positionX in the declaration of positionY is fine, because positionX is declared in the outer block.

Accessibility rules can seem very complex. The key is to remember the outer/inner block rule. The complexity comes in what how blocks are defined. We will visit block formation and accessibility in future chapters as we define new language constructs that can define blocks.

Assignment as an Operator

We have mentioned that the assignment operator is indeed an operator. This means that we can combine it with other operators in potentially confusing expressions. To make sense of this, we need to remember that, as an operator, assignment evaluates to the value from the right side of the = sign.

Consider this example.

int x = 10;

int y = x + 10 - (x = 5) - (x = 3);

In the evaluation of the expression, the first reference to x gives 10, the first assignment gives 5, and the second assignment gives 3. The expression therefore evaluates to 10 + 10 - 5 - 3 or 12. After the last statement, x will equal 3 (via the last assignment operator evaluated) and y will equal 12.

Exploiting The Rules and Making Big Messes

At this point in the chapter, we have seen some straightforward rules about C and expressions. We have also seen some interesting and odd combinations of expression shortcuts, type conversions, and precedence rules. If programmers are not careful with the code they write, they could be creating a big mess. The syntax rules are given for flexibility, but they can be exploited with some strange results.

To make code as clear and straightforward as possible, consider these programming guidelines:

Use meaningful variable names and expressions, even when literals will work. Words are much more meaningful than numbers and you should be using variables as part of the documentation of your code. Code like

circumference = 2 * pi * radius;is much clearer thancircumference = 2 * 3.14159 * 4;Use names for boolean values rather than literals. Using the name

truefor a value conveys a lot of information -- what types you are dealing with and the value you are using -- rather than using1.Use assignment operators as statements only, not in expressions.

As with many C constructs, being allowed to use assignments in expressions does not mean you should do it. Assignments in expressions is one of the most confusing syntax rules of C.Avoid using shortcuts in expressions. As with assignment statements, shortcuts are just too confusing to be used in expressions. Used by themselves as statements, shortcuts can be convenient and expressive. And even though shortcuts used to influence compilers when they generated instructions, few modern compilers pay attention to them anymore.

Limit all name access to the tightest possible block. Variables should be declared as close to their use as possible. Avoid global variables and stick with local declarations.

Use casting to make sure types are converted. Expressions can get complex and type conversion does not always work in the obvious way. When in doubt, use casting.

We could give many examples of convoluted C code. However, there is an annual contest to determine the most obfuscated C code written; see the Web site at ioccc.org for great example of obfuscated C code.

Comments and Documentation

One of the most important guidelines for writing good, understandable code is to document the code you write. C provides two mechanisms for inserting comments and documentation into your code.

First, anything on one line that is included after a "//" sequence is considered a comment and is ignored by compilers. So lines like

// x = x + 2;

means nothing, because it is ignored. Everything to the end of the current line is considered part of the comment.

The second mechanism for documenting is a "/*" ... "*/" sequence. Anything between the two symbol sequences is considered a comment and is ignored by the compiler. This can be a single line, multiple lines, or even just part of one line. Consider these examples:

/* This is a single line comment. */

/* This comment

spans several

lines.

*/

x = x /* small comment */ + 10;

Project Exercises

In this section -- for this and future chapters -- we will use projects that are comprised of existing code on GitHub. We will bring that code into the CloudPebble environment for examination and experimentation. Instructions on how to do this were discussed in Chapter 2.

Project 3.1

You can access the starting code for Project 3.1 using this link. When you have successfully brought the project into your CloudPebble environment, you can run the code. It implements a simple program with a ball bouncing up and down on the Pebble's display when you click the "select" button.

You can ignore a lot of the code in Project 3.1; much of it is required to make the program run on a Pebble watch. Let's start with the declarations. Consider the declarations for the X and Y positioning of the ball:

static int position_x, position_y;

static int x_velocity, y_velocity;

const int ball_radius = 10;

Now look at line 48. These variables are used to draw the ball and used to determine it's speed on the display.

Try these exercises using the code from Project 3.1.

Change the declaration in the code to make the ball bigger. Notice that the statement at line 48 uses the

ball_radiusvariable to draw the ball. Change this variable to make the ball bigger. (Keep it less than 30 or the ball won't bounce. Can you figure out why?)Now make the ball faster. The two velocity variables --

x_velocityandy_velocity-- are initialized at line 16. At line 36, the velocity is used to move the ball in the Y position (up or down) by changingposition_yvariable. Change the velocity to make the ball move faster.The ball only bounces up and down. Now add a line under line 36 to also change the

position_xvariable to that the ball will also move in the X direction.Look for the two functions listed below:

static void up_click_handler(ClickRecognizerRef recognizer, void *context) {

}

static void down_click_handler(ClickRecognizerRef recognizer, void *context) {

}

The code in these functions are run when the top and bottom buttons are pressed, respectively. Add some code to the `up_click_handler` function -- between the curly braces (`{}`) that will make the ball bigger when the button is pressed. You can do it in one line. Use the shorthand notation for incrementing a variable.

- If you simply try to increment `ball_radius`, you will have a compilation error. Why? Change the declaration of `ball_radius` to implement the up button click correctly.

- Do the same thing for `down_click_handler`, except make the ball smaller when you click the bottom button. Use the shorthand code for decrement.

- Now add a line to the `up_click_handler` function that also makes the ball go faster when you click the top button.

- Do the same thing for `down_click_handler`, except *slow* the ball down when you click the bottom button.

- Finally, add some comments to the file to claim the code as your own and to identify what you have done!

A completed project exercise for Project 3.1 can be found here.

Project 3.2

Now let's start a new project. Using this link, import Project 3.2 into CloudPebble and run it. You should get a letter traveling around a circle on the Pebble's display.

This code is a great example of expressions and of floating points vs integer computation. The main code we want to pay attention to is in the function move_letter():

angle = (angle + 1) % 360;

int dangle = TRIG_MAX_ANGLE * angle / 360;

position_x = center_point_x + (radius*sin_lookup(dangle)/TRIG_MAX_RATIO);

position_y = center_point_y + (radius*cos_lookup(dangle)/TRIG_MAX_RATIO);

Every time this code is run (when a timer goes off), the angle is incremented by 1. Notice that the modulo operator (%) is used, which advances the variable angle from 0 to 359, then starts over at 0. Also notice that the variable dangle is declared inside a block of code, showing that declarations don't always have to appear before code (but always before use).

The computations of position_x and position_y need some explanation. When we do computation on a Pebble CPU, we want to as much integer computation as possible. All the operations and variables are integers. Notice that we took special care to make the computation integer. We compute the dangle as an integer and we form sine and cosine computations as table lookups of precomputed values. These are all faster than doing floating point computations.

Why Are Floating Point Computations So Bad?

So why are floating point computations so bad to do on the Pebble smartwatch CPU? Floating point operations can be up to 3 times slower. First, floating point numbers are stored in an encoded form called IEEE 754 format. Every use of a floating point number means unpacking and repacking the values for computation.

Second, because floating point numbers have binary points and are stored with exponents, floating point computations can be very slow. Addition and subtraction have a long algorithm (see here for an example) and multiplication and division is even longer (this YouTube video is good at showing the long algorithm). Most CPUs that can handle floating point operations use an additional floating point coprocessor. The Pebble smartwatch CPU does not have that extra coprocessor, and in a CPU where we have to be very stingy about when to do floating-point operations, doing as much as possible with integers makes sense.

You will again find functions that implement the top and bottom buttons. Put code in each to move to the next letter in the alphabet and the previous letter in the alphabet when the top or bottom buttons are pressed, respectively.

Now add a line to the

up_click_handlerfunction that also makes the letter go faster when you click the top button.Do the same thing for

down_click_handleras you did in the previous exercise, slowing the letter down when you click the bottom button. What happens when you go too slow?Find the

select_click_handlerfunction. The code defined in this function will execute when the select (middle) button is clicked/pressed. Define a variable calleddirection(where would you declare this?) and initialize it to have the value1. In theselect_click_handlerfunction, "toggle" this to negative or positive on each click of the select button. Use thisdirectionvariable in the computation of the newposition_xto change direction of rotation when the select button is clicked.Add comments to the code to claim the code and to explain what it does.

A completed project exercise for Project 3.2 can be found here.